Drug Importation, Counterfeit Medications and the Pharmacist’s Liability: A Case Study and Legal Precedent

State bills which would allow wholesale drug importation have recently been proposed in Colorado, Louisiana, Oklahoma, West Virginia, and Wyoming, and recently-passed into law in Vermont. Not only could drug importation increase the risk of U.S. patients receiving dangerous counterfeit drugs, but it could also potentially expose pharmacists to liability for dispensing such counterfeit drugs.

Drug importation is not a new idea. For the past 15 years, leaders of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) have expressed concerns about counterfeit drugs sourced from foreign countries. Drug safety and the security of the drug supply chain are bipartisan issues that have led leaders from both sides of the aisle to be skeptical about drug importation.

An important factor in assessing drug importation proposals that often goes overlooked is the potential increased risk of liability for pharmacists who dispense counterfeit drugs. For example, let’s say a licensed U.S. wholesaler purchases a drug from a manufacturer or supplier in another country and sells the drug to a pharmacy in the United States. The pharmacist then dispenses the drug to a patient based on a valid prescription. It turns out that the medication is counterfeit, the patient is injured, and the patient sues the pharmacist and pharmacy that filled the prescription with the counterfeit drug. Pharmacists generally are not shielded from liability just because the drug was purchased from what purports to be a licensed wholesaler, though the scope and extent of liability varies by jurisdiction.

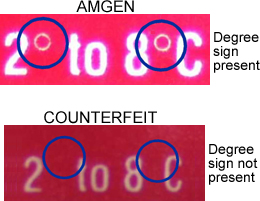

A case from 2004 points to real concerns by pharmacists about what can happen when counterfeit drugs make their way into the marketplace. As laid out in Fagan v. AmerisourceBergen Co., 356 F.Supp.2d 198 (E.D.N.Y. 2004), 16-year-old Timothy Fagan had an emergency liver transplant, and his doctor prescribed him a weekly injection of Epogen to treat his post-surgery anemia. On May 8, 2002, Amgen, the maker of Epogen, posted a letter on its website that said counterfeit Epogen had made its way into the U.S. drug supply. The letter stated that the counterfeit Epogen bore a lot number of P002970 and an expiration date of 7/03. The letter also explained that while Amgen’s vial label reads “Store at 2° to 8° C,” the counterfeit vials were missing the degree symbols.

On May 14, 2002, Fagan received a call from his pharmacy letting him know that counterfeit Epogen was in the marketplace. On May 15, 2002, he received his third delivery of Epogen, this time with the lot number P002970 (Exp. 7/03), i.e., the counterfeit drug he had been warned about. Shortly thereafter, Fagan noticed that the previous shipment of Epogen he had received in April also was missing the degree symbols. This shipment bore a different lot number: P001091 (Exp. 09/02). The Fagans alerted the FDA and Amgen that there may be additional counterfeit Epogen on the market. A few days later, Amgen also identified Lot # P001091 as counterfeit.

The counterfeit Epogen vials contained only 1/20th the amount of active ingredient as the authentic product. According to an article in Boston.com, the counterfeit drug left poor Timothy Fagan cramping after every injection and screaming so loudly at night that his seven-year-old sister covered her ears. No pharmacist would ever want to provide a patient with medication that would leave them in such pain, and no pharmacist would ever want to make the mistake that let those vials make their way into the hands of patients, but how confident could anyone be that he or she would see these missing degree symbols?

In this case, the court found in part that a pharmacy MIGHT be liable for counterfeit medicines if the two following conditions, among others, are met:

- There is a defect on the face of the counterfeit drug’s label, which means that the defect could have been discovered through reasonable inspection of that label, and

- A pharmacist failed to discover the defect.

In Timothy Fagan’s case, both of these conditions were met, though the actual defect in on the label was so small that there’s an appropriate question, not considered by the court, about whether this is the type of defect that should have been discovered through a reasonable inspection. This particular case ultimately settled out of court, but it shows that there is a potential path for a plaintiff to hold a pharmacy liable for harm caused by providing the patient with a counterfeit medicine. It does not matter if the drug comes from what purports to be a licensed wholesaler or if the drugs are purchased from a foreign pharmacy online, such as those that say they are Canadian.

The implications of Fagan v. AmerisourceBergen Co. are disquieting. Pharmacists should not put their patients or profession at risk by stepping outside of the United States’ secure drug supply chain. Pharmacists and pharmacy organizations oppose foreign drug importation because it is unsafe to patients and increases the risk of exposure to dangerous counterfeits. Proponents of drug importation should be transparent with the profession of pharmacy; their proposals may expose pharmacists and pharmacies to increased risk of liability for dispensing counterfeit drugs.

Kenneth L. McCall, Pharm.D

Associate Professor and Residency Director, University of New England College of Pharmacy

Board Member, The Partnership for Safe Medicines

Marvin D. Shepherd, Ph.D.

Professor Emeritus, College of Pharmacy, University of Texas-Austin

Board Member, The Partnership for Safe Medicines