Are you an advocate or legislator considering whether to pursue Canadian drug importation in 2021? Watch Importation 101 to learn the basics and get an update on states that have been trying to start importation programs.

Importation 101 for 2021

With the approval of the final rule for state drug importation programs (SIPs) last September, advocates and legislators are considering whether to pursue Canadian drug importation in 2021. And that’s understandable: the idea of importing drugs from Canada to lower prescription drugs costs has been floating around for about 20 years.

The truth, however, is that even though several states are pursuing Canadian drug importation, it is not and never has been a viable option. Watch our video to learn the basics and for an update on four states that have been trying to move forward with this idea.

Drug Importation in History

PSM has been documenting efforts to import Canadian drugs for 20 years. Past programs have not been successful. In the mid-2000s, Illinois, Minnesota, Maine and several other ambitious states tried to implement importation and found that their programs didn’t meet safety standards or save money.

Between 2003 and 2019, every head of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) refused to certify the safety of drug importation and U.S. and Canadian regulators, law enforcement groups, patient advocates, and healthcare professional organizations have agreed. You can read their reasons on our page, Statements Opposing Drug Importation.

In 2019, the Trump Administration posted draft regulations for state importation programs (SIPs), and solicited comments from stakeholders. Despite negative responses from pharmacists, drugmakers and distributors, as well as patient advocates in both Canada and the U.S., the administration released a final rule in September 2020.

- Failed importation schemes in Illinois, Minnesota, and Maine.

- Current Federal importation efforts, and state efforts in Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Maine, New Hampshire, New Mexico, and Vermont.

- Check the status of importation bills in state legislatures.

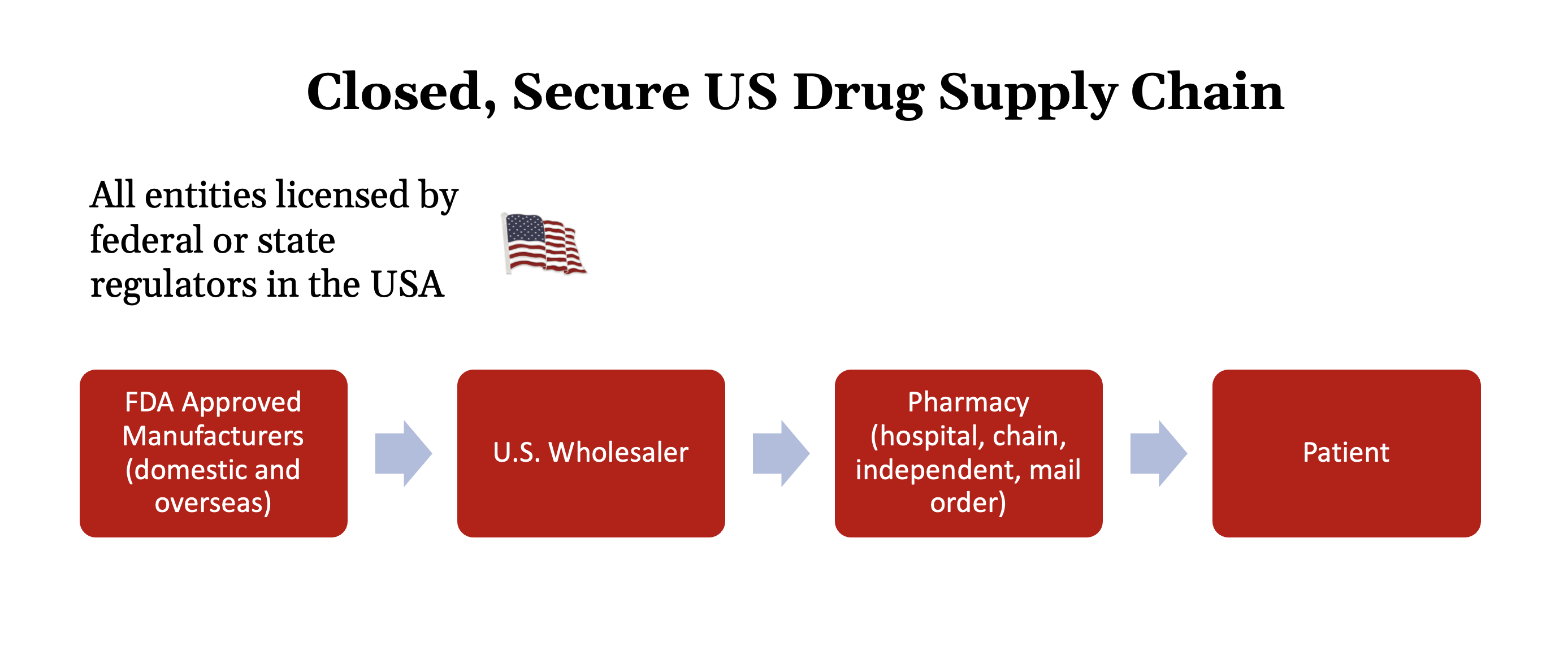

The Closed Supply Chain

This is how medicine comes to U.S. patients today.

Pharmaceutical manufacturers make products within the United States or in overseas factories inspected and licensed by the FDA. They import those medicines into the U.S. and sell them to licensed U.S. wholesalers. Pharmacists and other licensed professionals purchase medicines from those approved wholesalers and dispense them to patients.

Every entity in this process has a legal presence in the U.S.. If someone in the supply chain violates agreed upon regulations and standards they can lose their licenses and their right to do business in the U.S. And, if their actions merit it, they can be prosecuted in U.S. courts without having to cross national boundaries or negotiate with foreign governments.

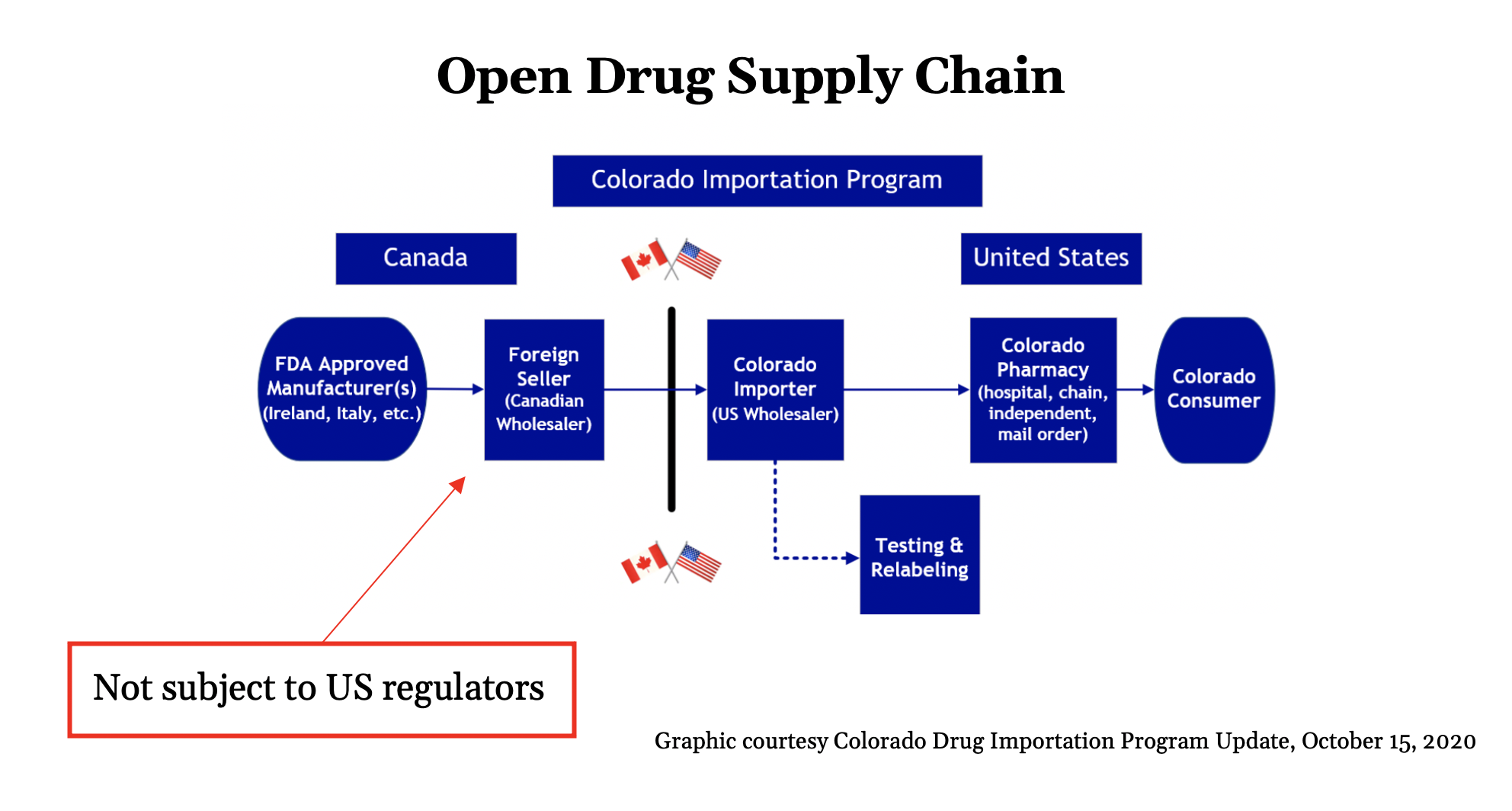

Canadian Importation: An Open Supply Chain

The supply chain Canadian drug importation advocates have proposed looks like this.

A Canadian wholesaler would buy drugs from a manufacturer and sell them to a licensed U.S. importer who has been contracted to acquire Canadian medicines for a state.

The importer would arrange for the drugs to be tested, repackaged and relabeled. Pharmacists and other health professionals would purchase the imported drugs and dispense them to patients.

This innovation looks like a small change that only introduces a little more risk. In practice, it’s more dangerous than it seems. Because Canadian regulators license the foreign seller, U.S. regulators have no authority over them. States could terminate a contract with a foreign seller, but they could not shut them down—and bringing a Canadian wholesaler to court requires permission from the Canadian government to extradite them.

Because some of the entities in this supply chain are regulated by a foreign regulator rather than a domestic one, we call it an open supply chain.

An Update on States Scrambling to Implement Importation Programs

Maine

Canadian importation will cost a $1 million more

Maine hasn’t submitted an application to HHS yet, but in January 2020 they held a hearing in which MaineCare’s Director of Pharmacy Operations reported that importation would not save the state’s Medicaid program any money. PSM submitted a Freedom of Access Request to see their data. When we examined it, we learned that once you factor in pharmaceutical rebates, Medicaid programs like Maine’s get medicine more cheaply than Canadian provinces do. Because medicine from Canada’s supply will not qualify for rebates, the 50 drugs Maine studied would cost nearly a million dollars more if Maine’s Medicaid program imported them.

Read more about the MaineCare’s price comparison document, or consult our overview on drug importation in Maine.

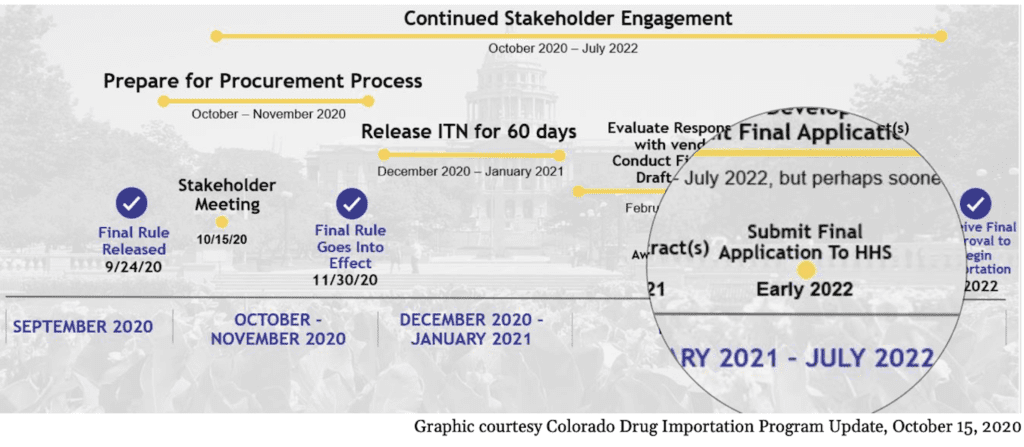

Colorado

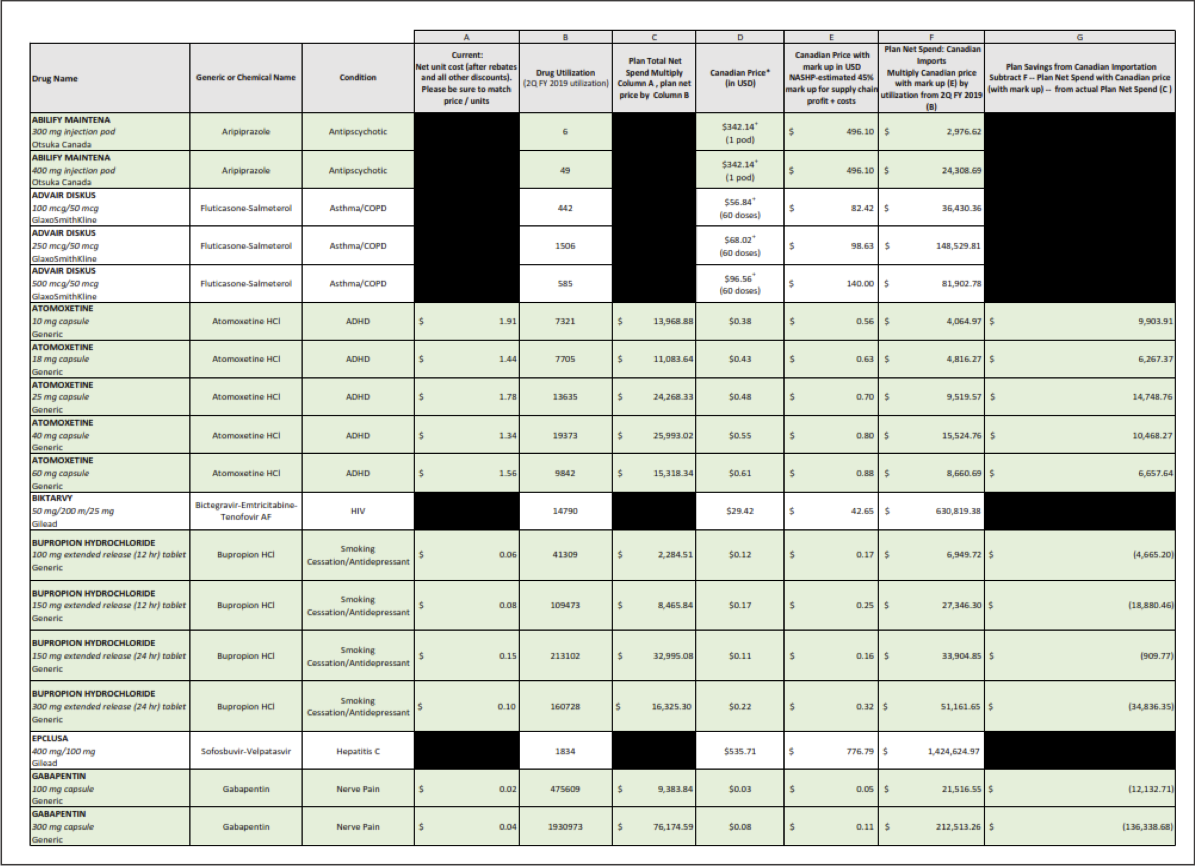

Could save $43 million by using U.S. generics instead of spending $1 million on plan development

Colorado spent a million dollars this year developing their importation plan. In October, they acknowledged that they won’t be submitting a plan to HHS until early 2022.

After a year of work, they still haven't secured a Canadian wholesaler—that's this year's millions of budget dollars—and they had to remove Medicaid from the plan because it already gets medicine cheaper than the Canadians do.

We also analyzed the list of medicines Colorado was considering for importation. We were puzzled that they were importing brand name medicines for which cheaper generics already exist on the U.S. market. We found that they could save $43 million in a single year simply by switching to generics.

New Mexico

Creating an opportunity for PBMs and insurance companies to make extra profits

After a year of work by staff in half a dozen state agencies, New Mexico released their draft plan and will probably submit their final to HHS any day now. They don’t have any Canadian vendors willing to participate, and like Colorado, they removed Medicaid from the plan because they already get medicine cheaper than the Canadians do.

There are a number of problems with their application, including the lack of liability protection for healthcare professionals who inadvertently dispense counterfeit medicines, and a failure to restrict pharmacy benefits managers, hospitals, and insurance companies from marking up the cost of Canadian medication until it’s the same price as U.S. medication.

Learn more about New Mexico’s draft plan in this video and its accompanying blog. Watch our Drug Importation in New Mexico page for updates.

Florida

Untested medication deemed suitable for Florida’s needy patients

Florida submitted its plan in late November, right after they circulated an RFP seeking a vendor to run their importation program. It paid thirty million dollars over three years, nobody bid on it. 10 million dollars a year wasn’t enough money to run the logistics, compliance, and customer support for the program. It didn’t include the cost of buying, testing, or repackaging medication.

How will your state justify spending money to hire a vendor to run a program like that in the middle of a pandemic?

As for the plan itself, Florida has not identified a Canadian vendor willing to participate, and they said they should not be required to test the medication they buy.

We’re honestly gobsmacked by this. Florida was ground zero for an enormous counterfeit medicine scandal that led to the creation of track and trace. How can they want to skip the testing step?

Canada Said No

At a macro level, Canada enacted new regulations in November that ban wholesalers from exporting any medication that might cause or exacerbate a shortage.

Canada’s drug supply is very small compared to the U.S.’s and they don’t make the majority of their own medicine. They are perpetually juggling shortages.

Since federal law only permits importation from Canada, and Canada has effectively closed the door on exporting their drugs, it doesn’t seem possible to implement this policy.

If you’re a legislator or advocate looking to address healthcare costs—and specifically the cost of medicine—this idea will burn tax dollars and you’ll have nothing to show for it.

Watch our video about Canada's response to drug importation schemes.

There Are Other Options

Regulate Pharmacy Benefit Managers. With the Supreme Court’s decision this last week in Rutledge v PCMA, states can now regulate how pharmacy benefit managers use spread pricing to extract profits from consumers and community pharmacies.

Promote Generics. As in the case of Colorado, above, we suspect that states may be spending millions buying brand name drugs when there are less expensive generics available. If Colorado could save $43 million in a single year simply by switching to generics (some of which are cheaper in the U.S. than in Canada) how much can other states save without compromising the safety of our supply chain?

See the latest importation news

at the Federal and state levels: Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Maine, New Hampshire, New Mexico, Vermont

at the Federal and state levels: Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Maine, New Hampshire, New Mexico, Vermont