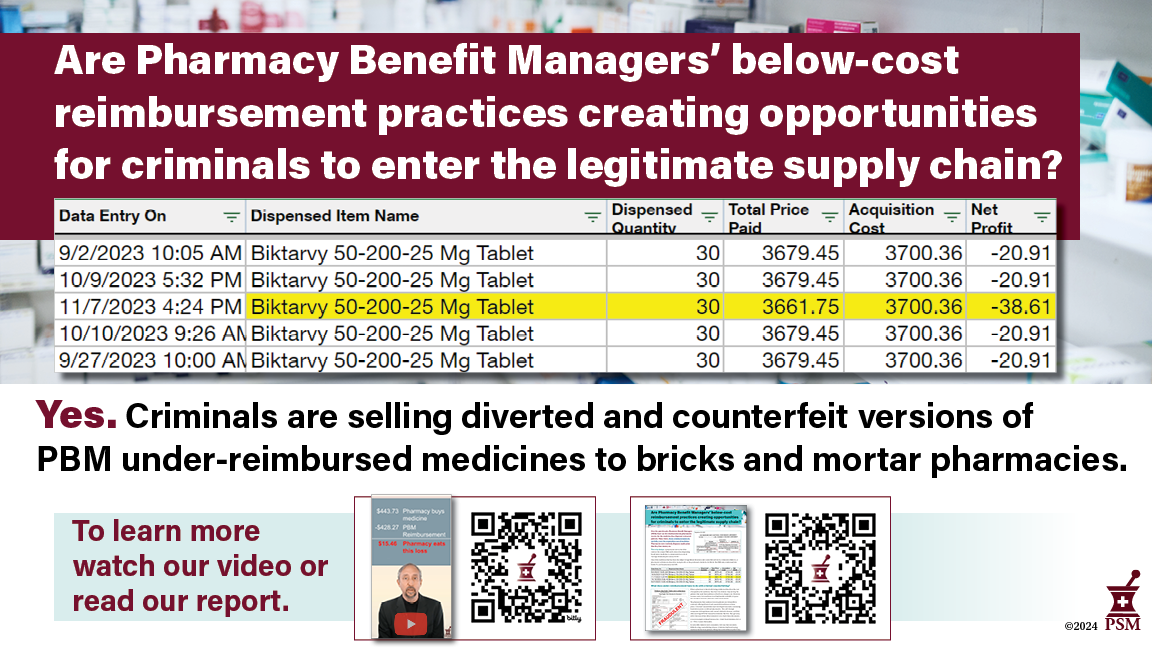

Are below cost reimbursement practices by Pharmacy Benefit Managers creating opportunity for criminals to enter the legitimate supply chain?

Whether it’s N95 masks, airbags, or helmets, demand for a product that the legitimate market cannot supply always creates a counterfeit market. Some kinds of markets, like regulated medicine, require very savvy criminals, but counterfeiters always find a way.

Historically, prescription medicine in the legitimate U.S. drug supply has been very safe. Strong regulation of the closed, secure drug supply chain and pharmacists’ attention to safety are a large part of why. Most pharmacies deal with one or two prime distributors, and only deviate when their traditional suppliers cannot fill orders due to medicine shortages.

However over the past few years, despite the development of the Drug Supply Chain Security Act, criminals selling diverted and counterfeit products have found buyers throughout the supply chain. What changed?

Watch our video and share these materials to raise awareness about this issue.

In a word: PBMs. (Pharmacy Benefit Managers)

Over the past decade, PBMs have been cutting the reimbursements pharmacies receive for the medicine they dispense to insured patients into smaller and smaller amounts. In many places, those reimbursements don’t fully cover the acquisition cost of medicine. Pharmacies now routinely dispense medication that they lose money on.

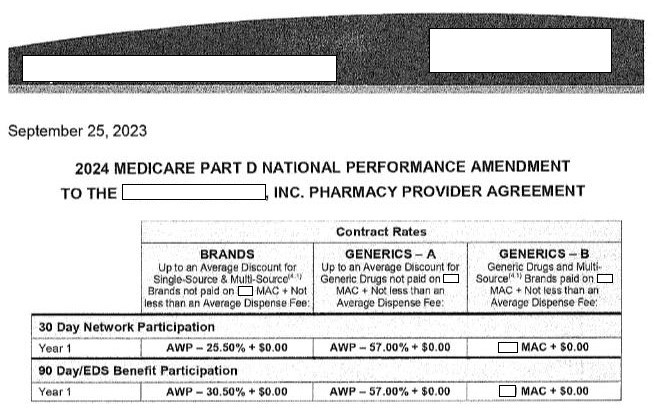

This is by design. A pharmacist sent us the 2024 contract for a major PBM and it shows that dispensing brand name medicines is compensated at a rate of “average wholesale price minus 25.5%.”

“No matter how brisk a business we do, pharmacies cannot sell enough generics, greeting cards, toiletries, gifts or knick knacks to make up the losses forced by [PBM] contracts.”

Deborah Keaveny, RPh, Owner, Keaveny Drug, Letter (November, 2, 2023)

Pharmacies that lose money by dispensing medicine must make up the difference in other ways and some losses are too big to cover.

We asked pharmacists to share their receipts with PSM to show what they paid for a medicine from their distributor and how the PBM reimbursed them. We found that PBMs are reimbursing pharmacies for less than the cost of medicines, which makes pharmacy buyers trying to keep their businesses afloat perfect targets for criminal counterfeiters trafficking cheaper, diverted and counterfeit medicine.

This 2-page summary explains the problems of PBM under reimbursements.

Share PSM's conference break slide to raise awareness in your community.

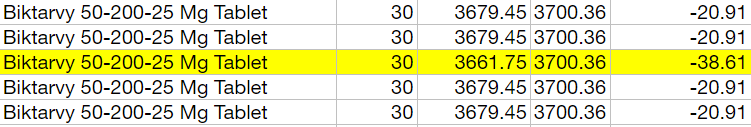

Example: Biktarvy

One of the medicines that’s been the subject of significant diversion and counterfeit activity by criminals is Biktarvy. This pharmacist in Delaware purchased it for $3,700.36. The PBM only reimbursed them $3,661.75, and they lost $38.

What do pharmacies do in this situation? Some go bankrupt or close, some sell their pharmacies to the chains, and some seek cheaper sources of medication. In the last few years, a lot of criminals who have been selling counterfeit and diverted Biktarvy were happy to talk to them. Below we profile a criminal ring that trafficked in hundreds of millions of dollars in diverted and counterfeit HIV medication.

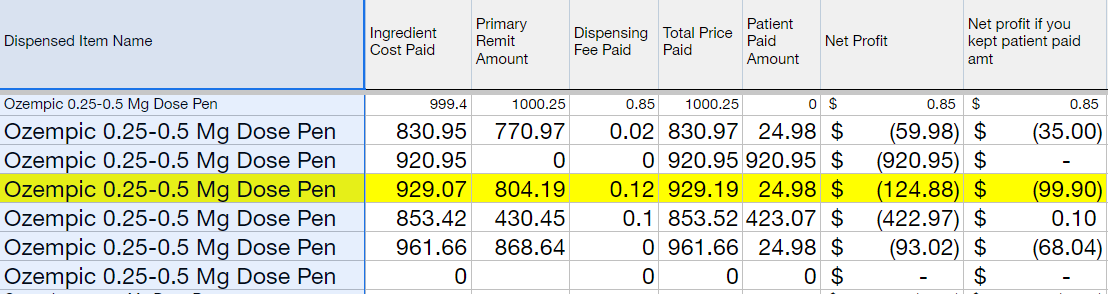

Example: Ozempic

In this example a pharmacist in Washington dispensed Ozempic to a patient. The pharmacy bought the drug for $929.07, and the PBM reimbursed them only $804.19. It’s not clear to us if the pharmacy kept the patient copay of $24.98, but even if they did, the pharmacy still lost nearly $100 dispensing this medication to the patient on behalf of the PBM.

Several pharmacists PSM spoke to have told their patients they cannot get Ozempic to fill prescriptions. What they don’t tell their patients is that they can’t obtain it at a price they can afford to dispense it at without losing huge sums of money.

This product is in high demand, and there is an active counterfeit industry supplying the global demand with fake versions. Noting that in our example above that U.S. pharmacies are losing money on Ozempic, we are disturbed but not surprised that the counterfeit Ozempic found in the United States was found in a retail pharmacy. PBMs are creating demand for Ozempic counterfeiters by reimbursing pharmacies below cost of acquisition.

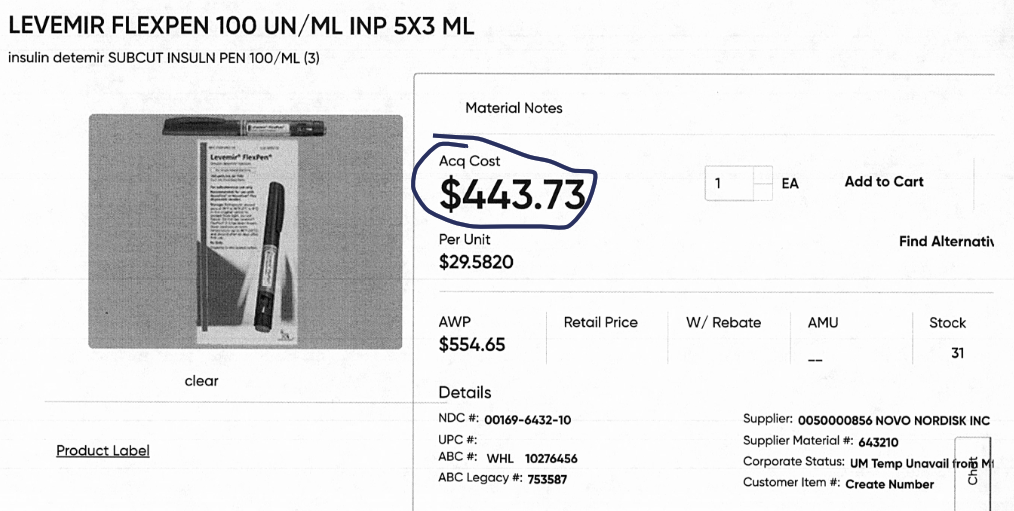

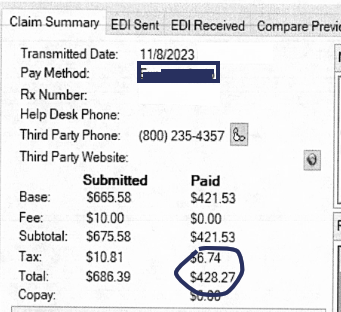

Example: Levemir

We are hesitant to include insulin because the Biden Administration’s $35 cap on insulin pricing for seniors on Medicare will be affecting costs through the supply chain for a while. However, pharmacists tell me it’s not unusual for them to lose money dispensing insulin. Here a pharmacy in Minnesota dispensed Levemir insulin to a patient. They bought it for $443.73, dispensed it to the patient, and were reimbursed $428.27, a loss of $15.46.

Insulin prices have been hotly debated for years, but it’s worth pointing out that it doesn’t matter if insulin costs $50 or $500 to a pharmacy. If the PBM pays you $15 less than your cost of acquisition their business practices will eventually bankrupt your pharmacy.

There is no category of medicine—brand name or generic— that pharmacies can use to offset these losses. Pharmacists lose money dispensing generic medications too. Those losses may only be a few pennies, but over 90% of the prescriptions they fill are generic, which means they lose a little money dozens of times an hour.

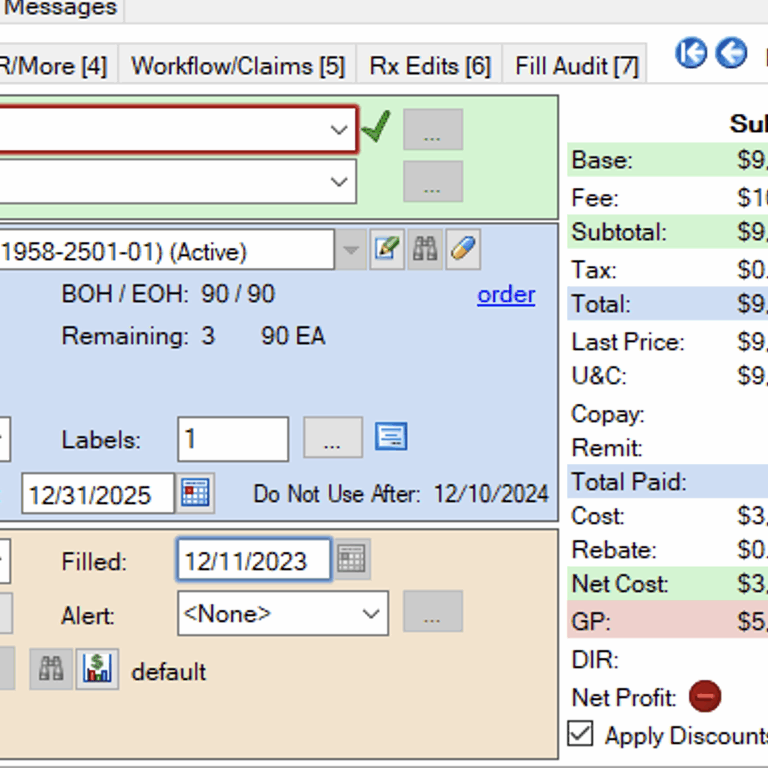

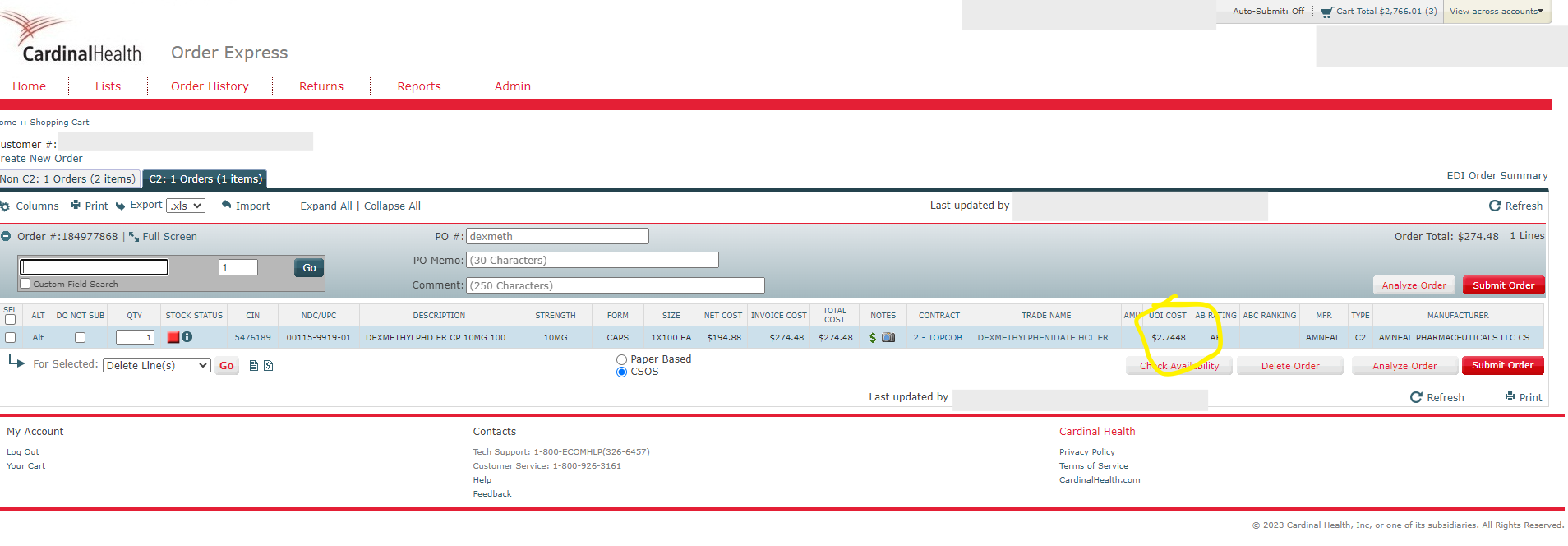

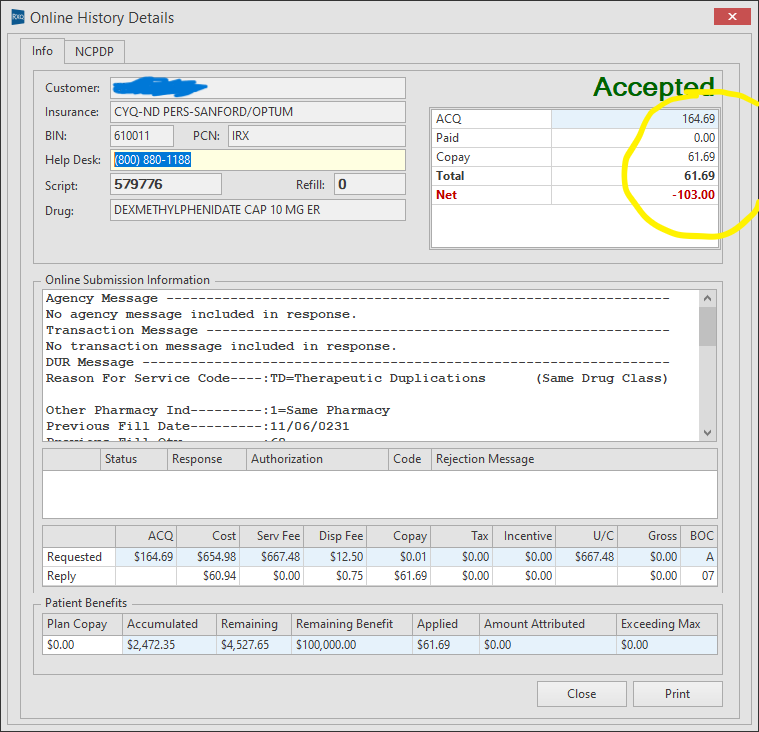

Example: dexmethylphenidate

Speaking of generic medicines, this pharmacist from North Dakota sent us this receipt for dexmethylphenidate, a psychostimulant used for attention deficit disorder. If you have a high school aged child, it’s likely there’s someone in their friend group taking it.

The North Dakota pharmacist showed us how he purchased 60 pills for $164.69 ($2.7448 / pill) and then dispensed them to the patient. The PBM paid him a dispensing fee of $0.75 and reimbursed him a total of $61.69, meaning he lost $103.00 on a single patient.

If you lose money on both brand and generic medications, how do you make money? In many cases, you don’t. You go out of business. Many pharmacy owners have sold or closed. This is particularly a problem when the pharmacy closing is the only pharmacy within 75 miles. Patients are simply left without a major part of their health care. Others have had to tell patients they couldn’t fill prescriptions that they lose money on. Those patients tend to leave, because they want to get their medicines in one place rather than making trips to multiple pharmacies all over town.

It’s not only reimbursement. PBM dispensing fees are often low, and sometimes they’re nonexistent.

Brick-and-mortar pharmacies must also maintain storefronts, store medicine and serve patients, all of which costs money. In fact, a 2020 study found that the average overall cost of dispensing a prescription was $12.40. Too often PBMs don’t compensate pharmacies for or under-compensate them for these operation expenses.

This means that many pharmacies that are losing money on prescriptions are also getting nothing for their overhead costs.

Why do pharmacies do business with PBMs?

You might why pharmacies enter contracts with Pharmacy Benefit Managers if they’re going to lose money. It’s a great question.

If you want to dispense medicine to a patient of XYZ Health Insurance Co., you have to sign a contract to agree to dispense medication for all their patients, for the medicines they cover, at the price they want to reimburse you at.

Almost all customers who fill their prescriptions have health insurance, and that medicine is paid for by their health insurance provider. But health insurers delegate the management of their prescription drug benefit to PBMs. In essence, the health insurers in the U.S. trust PBMs to manage how pharmacies get reimbursed, what patients pay for their medicine, etc.

And PBMs control quite a bit of it. In fact just three PBMs control 75% of the health insurance market. Even government programs like Medicare use PBMs to manage prescription drug pricing. If a pharmacy wants to give up PBMs, they also have to give up insurance companies. Very few people get healthcare without an insurance company providing it.

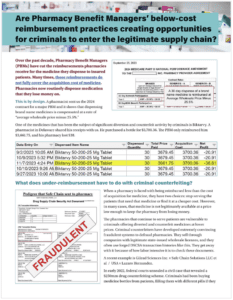

But what does all this under-reimbursement have to do with criminal counterfeiting?

When a pharmacy is faced with being reimbursed less than the cost of acquisition for medicine, they have two simple choices: stop serving the patients that need that medicine, or find it for a cheaper acquisition cost. But in many cases, that medicine is not legitimately available at a price low enough to make that reimbursement not a loss.

The pharmacies that remain in business are vulnerable to criminals offering medicines at lower prices than their usual distributors because they are losing money on PBM reimbursements. To their credit, many pharmacies have just shut down rather than take a chance with the safety of their medications.

Because criminal counterfeiters discovered they could not easily get pharmacies to trade safety for savings, they have developed extremely convincing fraudulent systems. These sophisticated fronts are designed to fool pharmacies into thinking they aren’t compromising safety while selling them diverted and counterfeit medicine. They sell through companies with legitimate state-issued wholesale licenses, and they often use forged DSCSA transaction histories. Here are two recent examples:

Gilead Sciences Inc. v Safe Chain Solutions LLC et al / USA v Lazaro Hernandez

In early 2022, federal courts unsealed a civil case that revealed a $250mm drug counterfeiting scheme. Criminals had been buying medicine bottles from patients, filling them with different pills if they were empty, cleaning them up to look new, and forging Drug Supply Chain Security Act paperwork to show a false ownership history. At the time the court filings were unsealed, over 85,000 bottles of medicine that treated HIV, Hepatitis C, and cardiac issues had been found within or had moved through the supply chain to patients.

Pharmacists believed that these medicines were safe because they came from state-licensed wholesalers and because they were bearing DSCSA traceability paperwork As the Wall Street Journal’s January 2022 article “Drugmaker Gilead Alleges Counterfeiting Ring Sold Its HIV Drugs” documents, the DSCSA showed the medicines to be fraudulently trafficked when pharmacists took the time to trace them. The goal of the fraudulent front was to discourage pharmacy buyers from conducting a labor-intensive trace investigation that would reveal the crime.

Many brick-and-mortar pharmacies bought these medicines thinking that they were getting bargains from licensed participants, and dispensed them to American patients. All these medicines, whether they were bought back from patients or wholesale fabricated from empty bottles, were unsafe to dispense.

Medicines such as the Biktarvy shown in the example above are among those being reimbursed below acquisition cost by PBMs and that explains why a pharmacist would be looking for a better price. If the pharmacist could get a better price while staying within the licensed supply chain and not lose money, why wouldn’t they?

USA v Boris Aminov

In this case unsealed in October 2023, three New York City pharmacy owners worked with co-conspirators to resell unsuspecting pharmacies HIV medicines they had purchased back from patients after they were dispensed. Nearly $10mm of this medication sold to pharmacies went through special pharmacy-to-pharmacy marketplaces that are not accessible to the public. Pharmacies struggling with pricing pressures are increasingly using these online marketplaces to look for bargains and hard-to-find medicines. They are vulnerable to criminal sales because they use an exception in the track-and-trace system to sell without providing transaction history showing where the medicine came from.

Pharmacy reimbursements should not be so low that they lose money

In every commercial setting, counterfeit markets arise when there is demand for products that the market can’t provide legitimately. Judging by the increasing number of unsafe products we are seeing in court cases, criminals are taking advantage of the reimbursement problem to defraud pharmacies with unsafe medications. They may not have created the under reimbursement problem, but they are certainly taking advantage of the situation to defraud pharmacies and patients.

During the COVID-19 pandemic we saw enormous counterfeit markets arise to supply everything from N-95 masks to testing kits because supply wasn’t available. Markets for counterfeits are created when existing supply cannot satisfy demand or, as we have shown, systemic changes increase demand for products at a cheaper price.

More recently, enthusiasm over injectable weight loss products (Ozempic and Mounjaro) has created a market for counterfeits. Limiting factors differ between countries but all create the demand for fake medicines. In the U.S., lack of supply, lack of insurance coverage, and poor reimbursement practices are driving demand. These are not necessarily the same factors that drive a counterfeit market for Ozempic in, say, Scotland, despite the fact that Scotland also has counterfeit Ozempic.

Many healthcare advocates representing stakeholders in the supply chain have decried the business practices of PBMs for putting pharmacies out of business, inserting an additional expensive middleman that wastes government healthcare dollars, or blocking access to cheaper generics of branded medications.

We can now add “increasing the chance pharmacies buy from less reputable vendors who might sell counterfeits” to their list of harmful consequences. We hope policymakers putting boundaries on the behavior of PBMs take note, because this is not just an economic dispute: these dynamics put all U.S. patients at risk.