How Upper Payment Limits on medicine increase the risk of diverted and counterfeit medicine in the drug supply

Several states are experimenting with Prescription Drug Affordability Boards (PDABs) to address the price of medicine. Every state has a different approach. Colorado’s PDAB evaluates medicines to classify them as either “unaffordable” or “not unaffordable” and then has the option to set an Upper Payment Limit (UPL) for:

- the maximum amount a pharmacy or provider can be reimbursed by an insurance company or PBM for the cost of the medicine they dispensed or administered; and

- the maximum amount a pharmacy or provider can pay to buy that medicine from a wholesaler.

This strategy presents a big problem for independent pharmacies because UPLs only set a ceiling on the amount a pharmacy can be reimbursed, not a floor. Pharmacies are already losing money on a wide variety of medicines because pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) reimburse them for less than it costs to buy the products from authorized wholesalers. This situation has created a risk to the drug supply chain as counterfeiters target pharmacies with diverted and counterfeit versions of under reimbursed medicines.

The goals of Prescription Drug Affordability Boards are laudable, but they are not achievable in their current form. State legislatures should go back to the drawing board on these bodies and renovate them.

PSM is particularly concerned about four scenarios

- Pharmacies that currently break even or better on medicines might find that the PBMs they dispense for lower their reimbursements to make up for profits they lose as a result of the UPL. Dispensing those medicines will go from being profitable to unprofitable, and criminals will aim to sell diverted/fake products to these pharmacies.

- Pharmacies that are currently losing money due to PBM under-reimbursements will face even greater financial pressure, and will become even more attractive targets for criminals selling black market medicines.

- Since World War II, price controls have repeatedly been associated with the creation of black markets, and black markets for medicine are particularly dangerous. Should Colorado put UPLs on medicine, several types of actors will be incentivized to arbitrage medicine out of the state of Colorado, which will harm Colorado patients. Colorado is unprepared to deal with this danger: there is currently no law enforcement authority in the state adequately resourced to prosecute significant diversion of therapeutic medicine.

- Setting UPLs is likely to reduce supply, as many wholesalers won’t be able to afford to sell UPL-regulated medicines in Colorado. In situations where medicines are in short supply, patients will order risky drugs from outside the legitimate supply chain. PSM has seen cases where they have received diverted and counterfeit products.

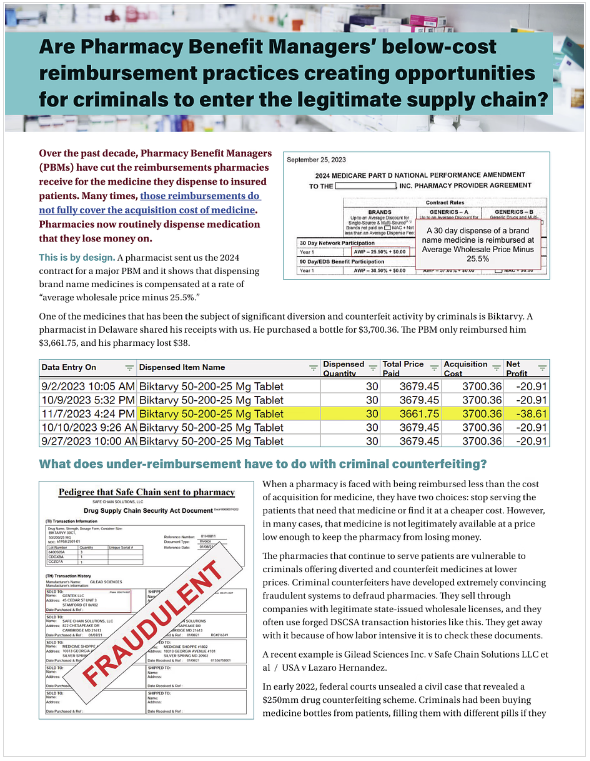

This 2-page summary explains the punishing effects of PBM under-reimbursements on independent pharmacies.

Upcoming PDAB action in Colorado

On June 7, the Colorado PDAB will be holding a hearing on Stelara, a drug for psoriasis and Crohn’s disease, to gather evidence about its “affordability.” Several PBMs already under-reimburse pharmacies for Stelara; the problem is so acute that many pharmacies PSM spoke to don’t dispense Stelara at all. That means that Stelara, like other medicines that pharmacies are forced to lose money on, is at high risk for diversion and counterfeiting.

A UPL in Colorado will raise this risk because nothing in the state’s Upper Payment Limit rule prevents an insurance company or PBM from reimbursing pharmacies below their cost to acquire the medicine. Pharmacies that make a small profit dispensing a medicine today could see those dispenses become money-losers. Pharmacies currently dispensing at a slight loss could see larger losses.

Upper Payment Limits for any medicine, including Stelara, will raise the current risk of counterfeits by making cheaper, diverted or counterfeit versions financially attractive when reimbursements drop below cost of acquisition.

Background: Medicines that are under reimbursed are at a high risk of being diverted and/or counterfeited

As PBMs reimburse pharmacies below cost of acquisition, criminal counterfeiters have been targeting those medications for fraudulent sale to pharmacies. From GLP-1 drugs like Ozempic to HIV medicines like Biktarvy, Descovy, and Genvoya, counterfeiters have been making and selling dangerous, fake, and diverted versions of these medications to unsuspecting pharmacies.

This danger isn't theoretical: In 2023, two men were jailed and a licensed distributor signed a multi-million dollar settlements for their roles in a crime ring that bought empty and diverted bottles of HIV medicines like Genvoya; cleaned them up, sometimes putting other, random pills in them; and sold them to unsuspecting pharmacies. Patients received and were harmed by the counterfeit products in these bottles. Genvoya was one of the medicines the Colorado PDAB recently considered for a UPL.

When a pharmacy discovers that medicine their patients need is being reimbursed at an amount below their prime wholesaler’s price, it is only rational that it would look for a lower price from secondary market vendors with wholesale pharmacy distribution licenses. Criminals in several unrelated cases have acquired valid wholesale licenses or worked with pharmacies to do informal wholesaling of diverted and counterfeit medicines through online pharmacy-to-pharmacy marketplaces.

Definitions

When we refer to counterfeit medicines, we mean fake pills or the wrong pills placed into convincing packaging that looks just like the correctly manufactured medicine.

Risk: PBM’s systemic reimbursement of Stelara below cost of acquisition creates a draw for criminals to sell diverted and counterfeit products to desperate pharmacies. Additional pressures from strategies like UPLs will worsen this situation.

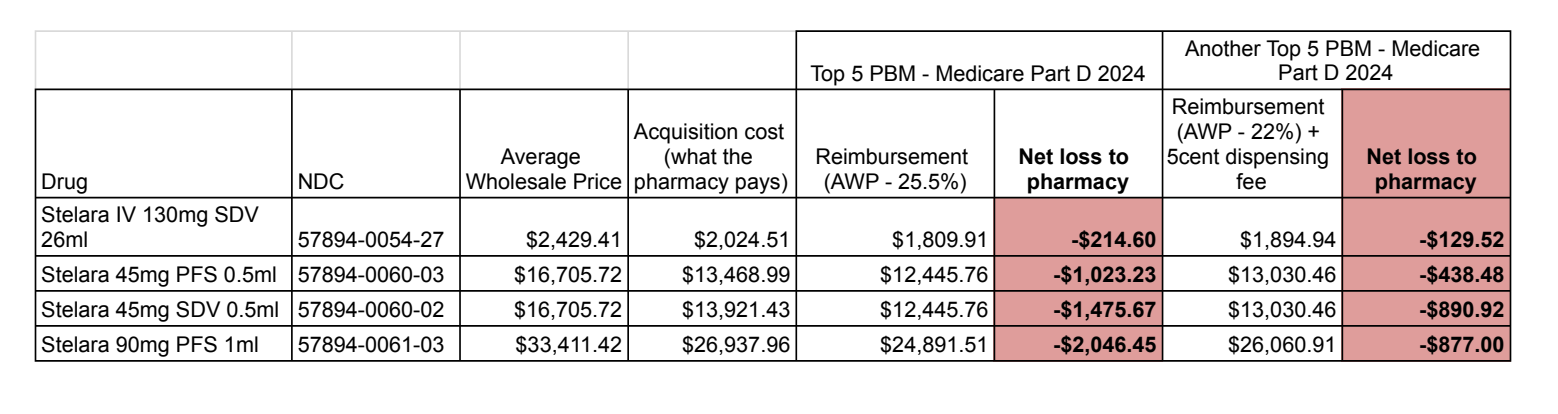

We pulled acquisition costs from several pharmacies around the country that dispense Stelara, and compared them to two PBM reimbursement contracts for Medicare Part D plans to demonstrate the problem. We have heard of pharmacies that have dispensed Stelara for a small net gain (<$20) but we could not obtain documented proof of that fact.

Click the image to enlarge it.

In all these cases the pharmacy loses money dispensing Stelara under Medicare Part D because reimbursement is below cost of acquisition. Because pharmacies that choose to dispense Stelara must find a cheaper source, they become excellent targets for criminals selling diverted or counterfeit products.

UPLs don’t address this problem, and have the potential to make it worse

UPLs are likely to have a very negative impact on independent pharmacies and their patients because the UPL rule doesn’t prevent pharmacies’ losses, and PBMs may lower their reimbursement amounts to compensate for lost profits as a result of the UPL.

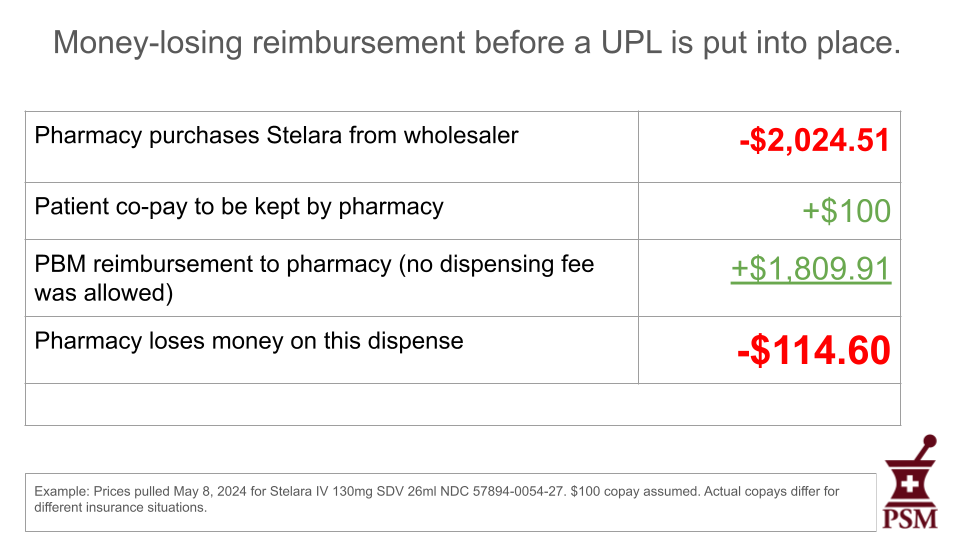

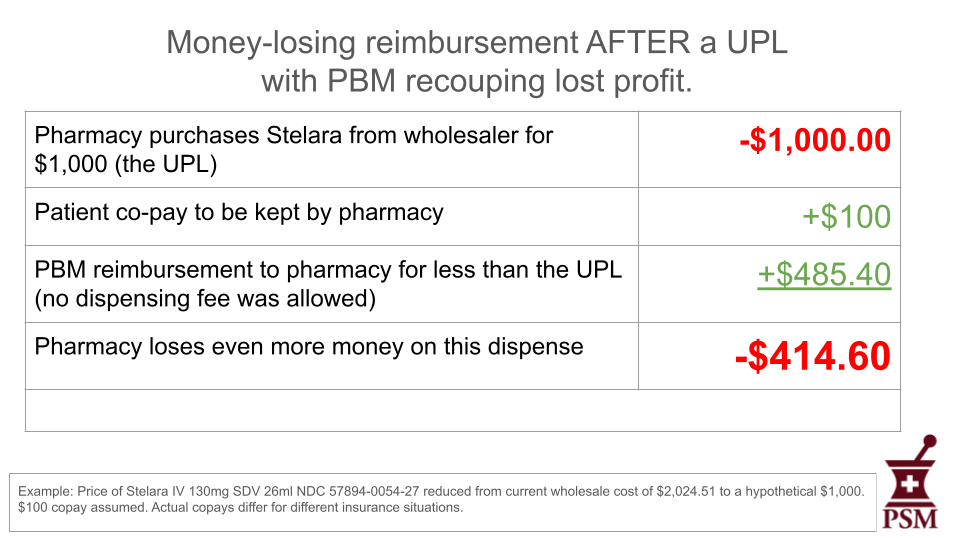

Using the data in the accompanying table, here is an example of a money-losing dispense on Stelara using the 2024 contract for a major PBM cited on our website.

No pharmacy can sustain losses like these, and nothing about the methodology of setting UPLs will improve this situation. Faced with these money-losing events, many pharmacies have told us they decline to dispense this medication. Others will become targets for criminal counterfeiters.

Won’t the UPL prevent PBMs from under-reimbursing pharmacies?

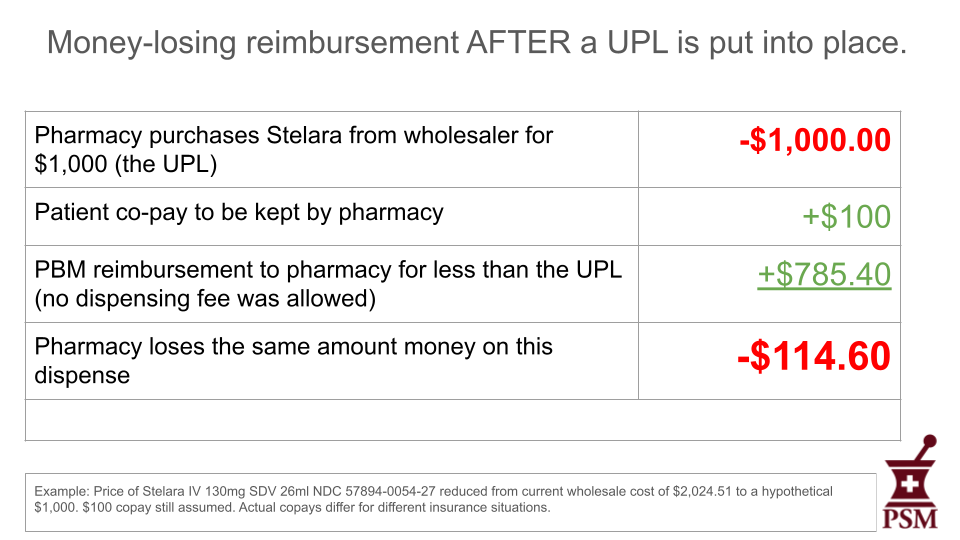

No. UPLs set a ceiling for reimbursement amounts, not a floor. They don’t set fixed prices for medicines. As things currently stand, PBMs will continue to profit on “spread pricing,” pocketing the difference between the price they have negotiated with the manufacturer and what they pay the pharmacies they under-reimburse, even under a UPL regime. Here is a hypothetical example in which the state has set a $1,000 UPL for the previously mentioned Stelara.

As you can see in this example, the financial impact of the drug is unchanged for the patient under a UPL. As with before the UPL, the pharmacy suffers a $114.60 loss because the UPL doesn’t prevent the PBM from lowering its reimbursement.

The final example shows that the PBM could reduce their reimbursement to the pharmacy even more to recoup some of the profit lost because of the UPL.

But won’t the dispensing fee keep the pharmacy from losing money on the dispense?

The rulemaking for Colorado’s UPL specifically says that:

An upper payment limit established by the Board does not preclude a pharmacist or pharmacy (as defined by section 12-280-103(43), C.R.S.) licensed by the State Board of Pharmacy to charge reasonable fees, to be paid by the providing health benefit plan of the consumer, for dispensing or delivering a prescription drug for which the Board has established an upper payment limit.

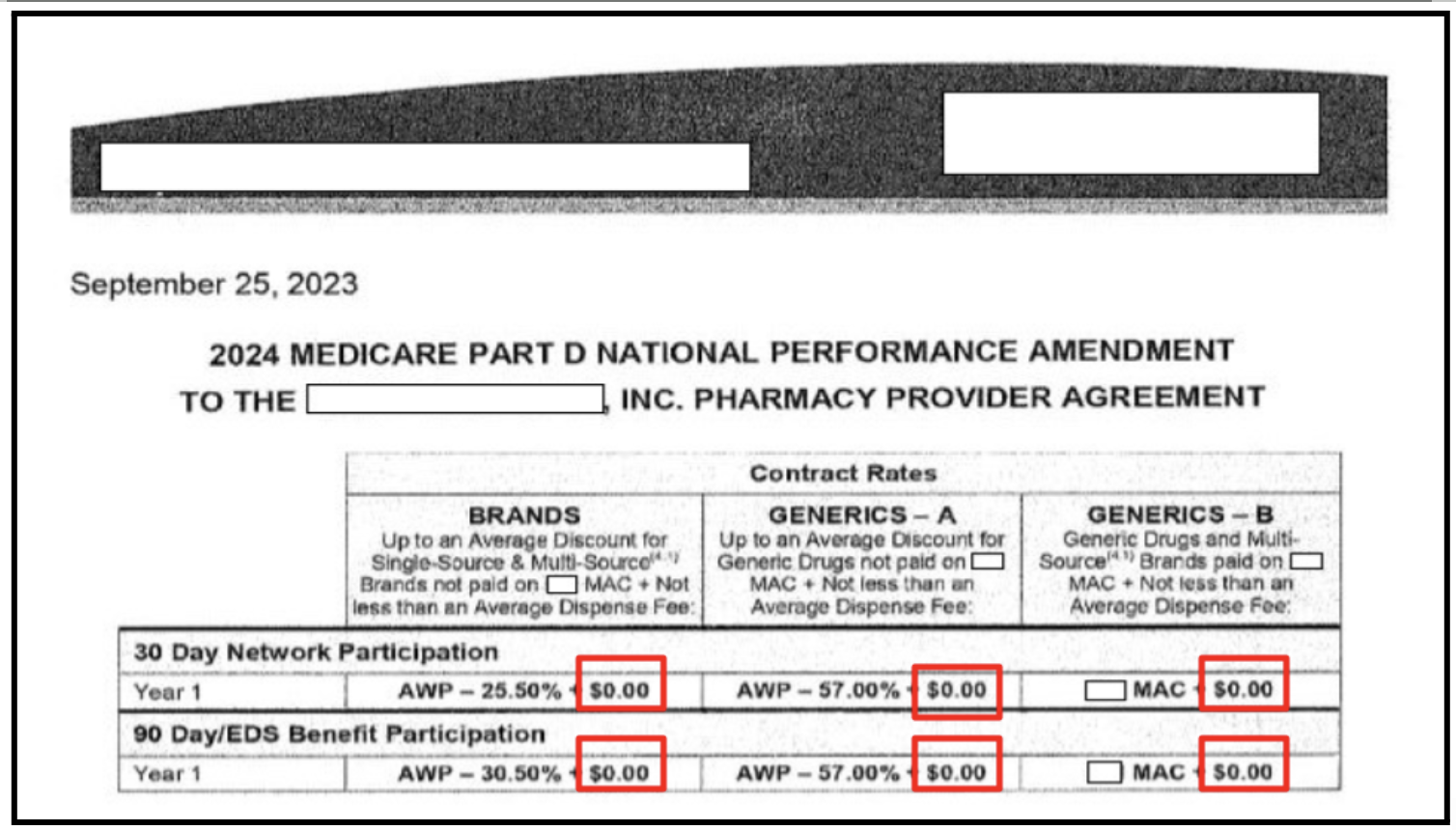

The rule allows pharmacies to charge fees that cover dispensing costs, but it does not guarantee that they are entitled to receive the fees. Dispensing fees are governed by contracts between PBMs and pharmacies, and current contracts often exclude them or offer token amounts.

This example is from a redacted top five PBM contract for pharmacies to fulfill Medicare Part D contracts for 2024. In all six instances outlined in red, no dispensing fee is included.

Pharmacists have told PSM that these PBM contracts are non-negotiable and we have documented many transactions in which a PBM paid no dispensing fee to the pharmacy or paid a token amount, such as $0.10 on a $900 medicine such as Ozempic.

The dispensing fee is not a small thing, because pharmacies don’t just buy and sell drugs. They also require staff and equipment to properly care for patients and their medicines.

Enbrel, Stelara, and Cosentyx, are all injected specialty medicines that have been or are being considered by the Colorado PDAB. These medicines require significant patient counseling that is more complex than asking a pharmacist whether to take a medicine on a full stomach. There are medicines and medical conditions that are contraindicated for patient safety. Patients who have not been trained to inject themselves will have questions and require significant assistance. All this will be done by a trained pharmacist, and that costs the pharmacy money.

All three of these medications require refrigeration and are sensitive to motion. They need to be handled and stored carefully. These refrigeration units, though shared with other medicines, are also not free.

Industry analysis from 2020 found that dispensing the simplest of medicines costs pharmacies at least $12. For specialty medicines such as Stelara, that cost is closer to $73. Pharmacists typically do not get a $12 dispensing fee to cover these costs, much less one that would cover a loss in the cost of medicine acquisition. Even if a pharmacy were reimbursed at cost for a medicine, they would lose money in the process of dispensing it.

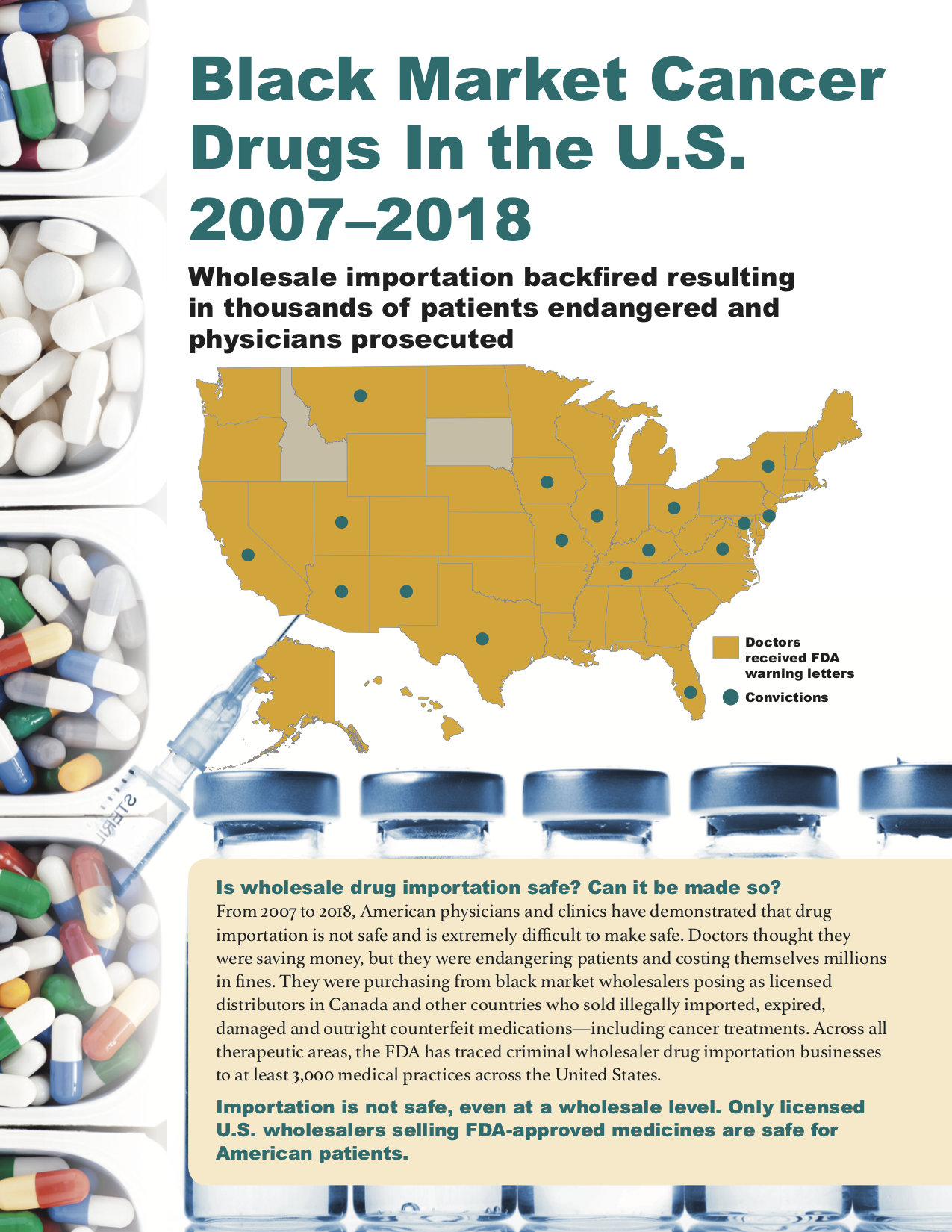

Have providers of other specialty medicines in the U.S. been defrauded by criminals selling counterfeit medicines before the rise of PBMs?

Yes. From 2007 to 2012, a Canadian online pharmacy called Canada Drugs trafficked $78 million in black market and counterfeit oncology products through wholesale channels, almost exclusively to oncologists who administered them in-office. They targeted independent oncologists working outside of hospital systems, presumably because they wouldn’t have to deal with purchasing departments concerned with compliance. The Canadian criminals even sold through U.S.-based sales offices and staff, so physicians would think they were buying from American sources. This PSM publication describes many of the legal cases that encompass this era.

From 2009 to 2013, 39 individuals were prosecuted for the purchase or sale of non-FDA approved intrauterine devices (IUDs). In Texas alone, over 450 black market IUDs were provided to Texas patients. Patients in 7 states were affected. There were six separate lawsuits brought for patient injuries in Arkansas alone. Some patients experienced long lasting medical adverse events.

Risk: Arbitrage and diversion of medicine from Colorado

Attempts to control the increased prices for products often distort the market in ways that don’t benefit consumers (see “Why Price Controls Should Stay in the History Books,” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis). A UPL is a price control, and if a UPL creates a guaranteed supply of a medicine cheaper than can be found in every other state besides Colorado, an immediate black market in Colorado-priced medicine would emerge. The incentive for everyone allowed to buy UPL-price-controlled medicine would be to sell it everywhere else in the U.S. except Colorado.

Existing examples suggest that pharmacies, which are already facing tremendous financial pressure, would make more money selling medication to pharmacies out of state than dispensing it within Colorado. These examples include:

Arbitrage of medicines in shortage: PSM has studied the gray market in lidocaine, an injectable anesthetic available from multiple manufacturers that is currently in shortage. Following a tip from a hospital pharmacy in West Virginia that was forced to purchase lidocaine for a 500% markup over its regular wholesale price, PSM found a small community pharmacy in Texas that had adopted an arbitrage model where it purchased lidocaine injections that it never intended to dispense for the purpose of selling them to a licensed gray market wholesaler. This was happening at the same time physicians in Texas were struggling to get lidocaine for orthopedic arthritis patient injections. (See: “Why pay 500% markup for lidocaine?” on PSM’s YouTube channel)

Pharmacy-to-pharmacy online marketplaces: Technically, it is legal for pharmacies to sell each other product without track and trace documentation for a named patient need. This is an important way for pharmacies to address shortages. Online marketplaces, like Amazon marketplace but for pharmacies, have sprung up to facilitate these transactions, and are an obvious route that pharmacies and wholesalers with access to cheap UPL-governed medicine could use to sell price-controlled medicine out of state.

Additionally, we have seen examples for over two decades of patients who sell their medicine to criminal diverters who bring it back into the supply chain illegally. This is likely already happening in Colorado for Medicaid patients. (See PSM’s video, “Pharmacists: How to spot a patient fraud”)

UPLs for medicine would create the unintended consequence that it is more profitable for any player in the supply chain to sell that medicine outside Colorado than to dispense it. Even if only one or two supply chain participants did this, it would have an outsized effect on patient access. The resulting shortages would worsen access to that medicine, fueling additional risky behavior on the part of patients.

We understand that this is not the intended goal of the Prescription Drug Affordability Boards like Colorado’s, and we sympathize with the challenges of making change in a complex economic system. However the warning signs of the unintended consequence of a black market are very clear. Furthermore economists who study black markets created by price controls recommend that the government instituting them create and fund an entity that enforces the rules around these controls. Colorado has no such entity, and even if one may assign that responsibility to an existing entity, there is no funding allocated to protect patients from these unintended consequences.

Risk: Unsafe patient behavior

When patients have difficulty getting the medicine they need, they engage in unsafe behavior to get it. This isn’t theoretical. We have a recent example.

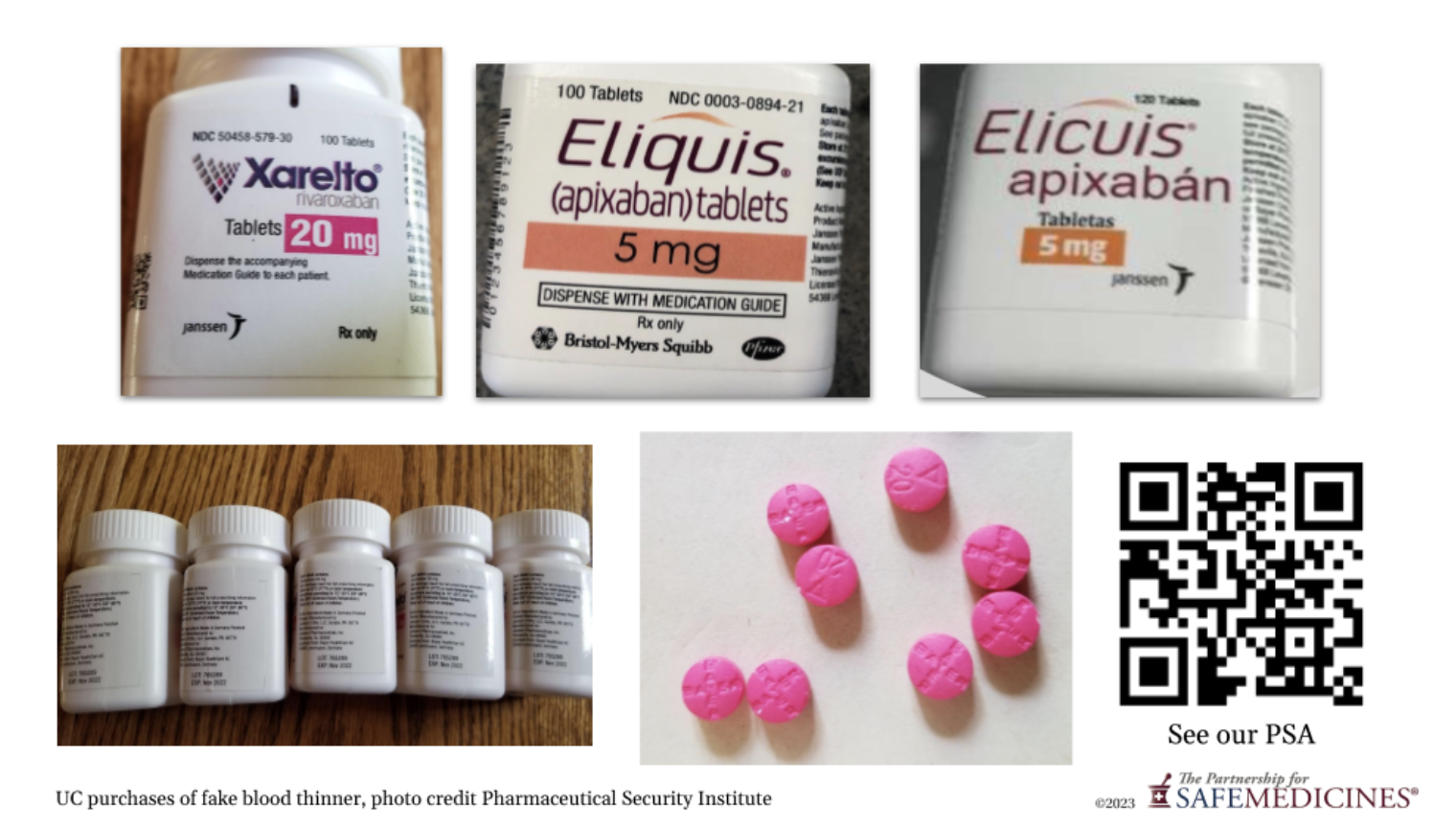

In November 2021 one of the top five PBMs removed one of two state-of-the-art anticoagulants from their drug formulary. These new products, Eliquis and Xarelto, are successors to warfarin, which requires more monitoring and blood testing.

The formulary change forced nearly 100 million U.S. patients into a non-medical switch. For many medicines, this is a problem. Physicians and patients often work together to find the exact right dosage of a medicine that is therapeutically effective, and once found, any change could result in therapeutic failure. Examples of therapeutic failure for anticoagulants, which include deep vein thrombosis, blood clots, and stroke, are extremely dangerous for patients.

Mexican counterfeiters enter the market to meet patient need

Soon after the PBM removed Eliquis from their formulary, PSM received word that placebo counterfeits of Eliquis and Xarelto had been found in border pharmacies in three cities in Mexico, including Los Algodones. These pharmacies cater to U.S tourists and are often within a short walk or drive from the border checkpoint. Los Algodones, for example, is a twenty-five minute drive from Yuma, Arizona and a three hour drive from Phoenix.

The examples that undercover purchasers working for manufacturer anti-counterfeiting teams found were extremely good-looking fakes.

As you can see in the examples, the first two instances of these fakes are labeled in English. The medicines themselves were nothing but filler powder. They contained no active ingredient at all. The third medicine was the same product, but a counterfeiter had translated the label into Spanish to outwit clever Americans who might wonder why an English-labeled FDA-approved product was for sale in a Mexican pharmacy. It, too, contained pills with no active ingredients.

Manufacturers of the legitimate products learned about these fakes when concerned patients called in to their quality hotlines. Patient harm was reported, but not publicly documented. These fakes spread along the Mexican border pharmacies until they finally reached Cancun. In June 2022 the PBM put Eliquis back on their formulary, reducing the need for patients to seek alternative sources. Anti-counterfeiting team members told me that after that, the fake anticoagulants were no longer easy to find in Mexican border pharmacies, though you can still find black market versions for sale online.

The criminal black market is absolutely responsive to economic conditions that affect patients. If anything reduces access to Stelara or any other UPL-regulated medicine in Colorado, the black market will step in, likely with unsafe medicine.

Because prosecutions of counterfeit therapeutic medicines are not well-funded or a high priority, it would be wise to tread very carefully when making policy decisions that might result in reduced access to medicine.

Conclusion

Today, the dysfunction of how medicine is paid for in the U.S. healthcare system creates an incentive for criminals to bring black market versions of some medicines into the legitimate supply chain. Prescription Drug Affordability Boards do not do their work in a vacuum and must take into account existing conditions of the market to avoid unintended consequences from their policy work.

While the goals of Prescription Drug Affordability Boards are laudable, the problems in our healthcare system are complex, and using payment caps in just one part of the supply chain, on the supply chain participant least able to control prices, will yield multiple different unintended consequences.

Upper Payment Limits have many flaws and are unlikely to lower the price of medicine, but they are likely to reduce access and encourage a black market in medicines subject to a UPL. This will do more harm than good to patients, and that is the opposite of the stated mission of Prescription Drug Affordability Boards.