A peek inside a prescription drug diversion ring

One of the most thrilling true-crime stories of health care fraud isn’t on the New York Times Best Sellers list – it’s the indictment and pre-sentencing memo from the Southern District of New York’s prosecution of Boris Aminov. These documents are a “how-did-they-do-it” guide to prescription drug health care fraud, capturing text messages, crime photos, and a step-by-step guide to the deceit.

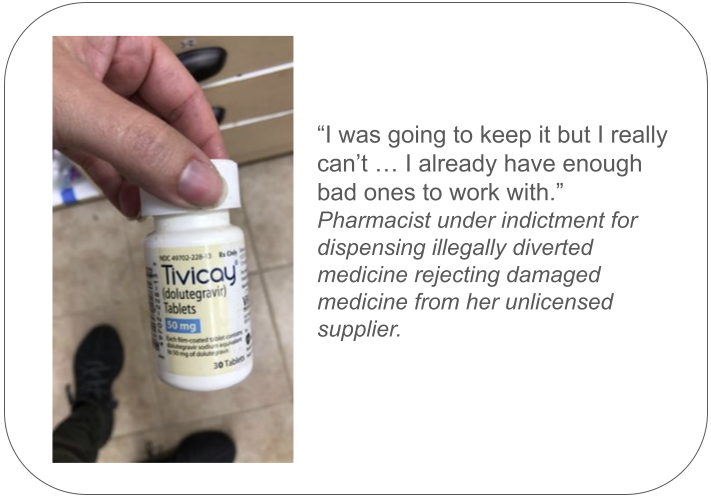

The Department of Justice says Aminov paid cash to buy medicines from patients on public assistance, sold the beat-up bottles to pharmacies for a fraction of what the medicine would have cost from a legit wholesaler (he wasn’t legit), and then the pharmacies illegally dispensed it to patients. The pharmacists sometimes complained they couldn’t use the bottles that were damaged.

Source: Sentencing Memo, USA v Aminov

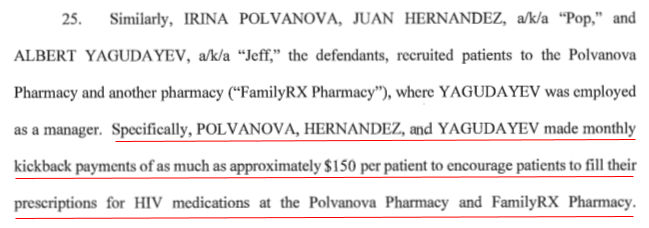

The defendants allegedly paid patients kickbacks of as much as $150 so they would fill prescriptions at their pharmacies.

Source: Superseding Indictment, USA v Aminov

The economics of the black market

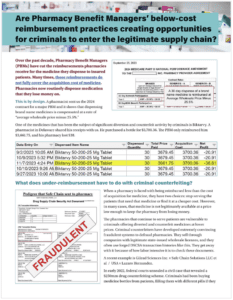

How could these pharmacies afford to pay patients lucrative bonuses? Pharmacists don’t make $150 off HIV medicine – they’re often reimbursed below cost – nor do they get that amount as a dispensing fee. That’s completely laughable. That’s what the two court documents explain – the pharmaceutical black market. They allow us to piece together the economics of this sort of crime.

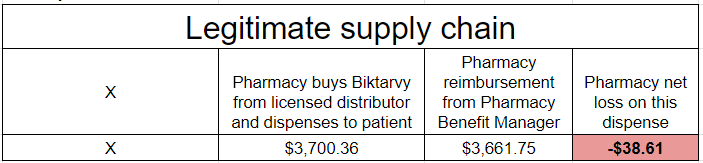

Take Biktarvy, for example. Here’s a transaction for Biktarvy that a pharmacist shared previously with us: The pharmacy bought a month’s supply of Biktarvy from a licensed distributor and lost almost $40 when the patient’s pharmacy benefit manager reimbursed it below the cost of acquisition.

Real life example of under-reimbursement by a PBM. See here for more information.

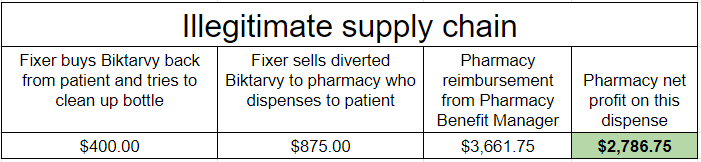

For comparison, when a criminal fixer buys it from a patient, sells it to a pharmacy, and (as the DOJ alleges) the pharmacy illegally dispenses it in this case, the pharmacy makes nearly $2,800 on it. In that scenario, it makes financial sense to pay a patient $150 to fill their prescription at your pharmacy – because you’re making so much more selling the diverted meds.

Example of profit chain for drug diverter and alleged pharmacy in USA v Boris Aminov.

Pricing obtained from the indictment and pre-sentencing memo.

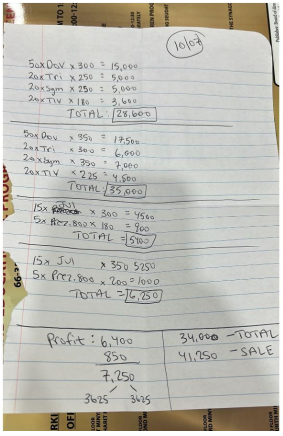

It’s not just Biktarvy. The sentencing document shows Aminov sold many medicines to pharmacies at black market prices: Juluca ($350), Genvoya ($875), Symtuza ($250), Triumeq ($300), Odefsey ($1,000), Prezcobix ($800), Descovy ($350), Tivicay ($225).

Hand-written receipt for medicine allegedly sold to a pharmacy

(Source: Sentencing memo, USA v Aminov)

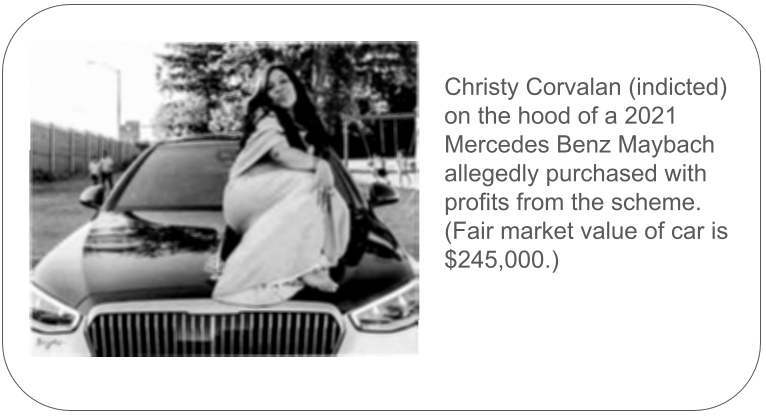

According to prosecutors, the pharmacists made as much as $3,000 per transaction dispensing these diverted drugs to hundreds of patients. The DOJ alleges the defendants defrauded Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurance companies to the tune of $20 million. The defendants allegedly bought luxury cars and waterfront property that are listed in forfeiture allegations.

Image: Superseding Indictment, USA v Aminov

How criminals sneak past honest pharmacists

Aminov didn’t have a wholesale license and he was selling at “too-good-to-be-true” prices, but if he wanted, he could have garnered a Board of Pharmacy-issued wholesale license, sold the medicine for $50 below cost instead of $2,800 below cost, and snookered law-abiding pharmacies. Others have done so, though not cleverly enough to avoid civil and criminal consequences.

This would have been necessary because on the whole you don’t see a great deal of pharmacies breaking the supply chain like this on purpose. Most pharmacists have a great spidey sense about spotting too-cheap-to-be-true medication. You have to defraud them by sneaking this stuff in and the smaller number of pharmacy prosecutions, vs physician prosecutions, really bears out my point.

The recent indictment of Scripts Wholesale in Brooklyn shows the danger to pharmacies. New York-based Scripts is licensed in other states so the company can sell throughout the U.S. Scripts is accused of distributing illegally diverted life-saving medication.

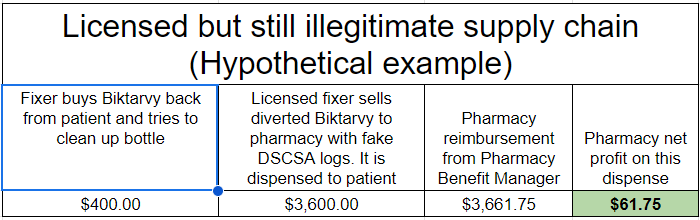

Imagine if a criminal didn’t take the Aminov route. Imagine that instead of selling a pharmacy a $3,661 medicine for $400, they sold it for $3,600 – $61 below reimbursement? Is a slight discount less suspicious? If you think the answer is yes, you now understand how almost $9 million of these medicines were resold through online pharmacy marketplaces. If you price your medicine high enough, it’s not as suspicious.

Our hypothetical example based upon recent counterfeit and diversion incidents.

If a pharmacist is making $61, is that suspicious? We all agree making $2,800 is too good to be true, but $61? What if they went to $30? With a wholesale license and believable pricing, schemes like this can really fool conscientious pharmacists.

Money laundering

Several defendants are still in court, but Aminov recently pleaded guilty to one count of conspiracy to commit health care fraud. It's a predicate crime that allows a charge of money laundering.

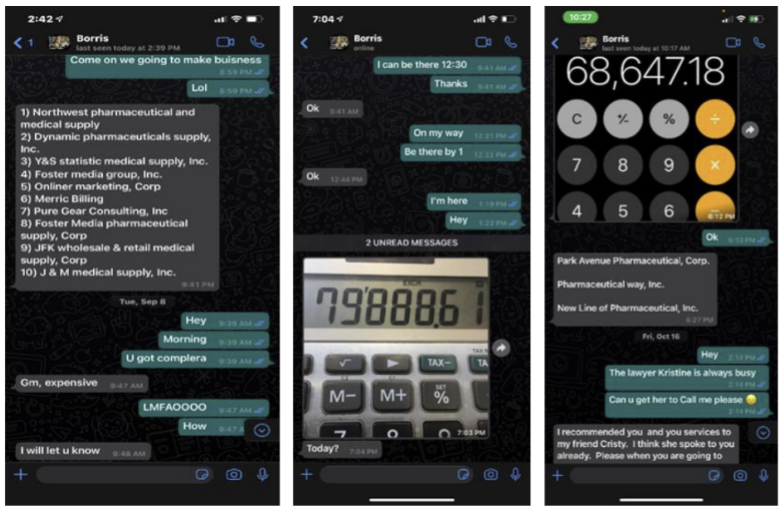

After delivering the diverted meds to his alleged pharmacy co-conspirators, Aminov gave a list of shell companies to his pharmacist compatriots so they could divide and better hide all transactions. That certainly made tracing the money easier for investigators during the money laundering Placement phase, when a criminal first puts the ill-gotten funds into the financial system.

Source: Sentencing Memo, USA v Aminov

And a shout out to law enforcement

This sentencing memo describes how the basis of the crime is accessible and applicable to the general public. In cases where the defendant is a licensed medical provider, as with the case of Dr. Lindsey Marie Clark, these details are useful for eventual licensing board hearings that follow any criminal process.

PSM and other advocates will also use the details in Aminov’s sentencing memo to teach pharmacists and patients about medicine safety and the tricks criminals use to defraud pharmacists and patients. We thank the unappreciated DOJ attorneys for their diligence on this case.

This also underscores the need to reform the pharmacy benefit manager (PBM) industry. Pharmacists will say it’s for their survival, and that’s true, but under-reimbursement practices create market opportunity for criminals like Aminov to break into the supply chain. That hurts everyone who takes medicines.

This content made its first appearance on our executive director's LinkedIn. Follow Shabbir Safdar and our own LInkedIn account for the latest in drug safety news.

More from PSM

Read documents from Aminov's case in our Prosecution Document Library. (We will post more as they become public.)

Consult our discussion of the impact of under-reimbursement on drug safety, or read the summary.

Learn about another high-volume black market HIV drug ring that was first identified in Gilead Sciences v. Safe Chain Solutions.